We are women scientists – hear us ROAR! Or, at least watch us discover some stuff! That’s right, we’re embracing our roots and taking a new turn with our blog to feature women in science. Ladies of the lab coat often times don’t get the credit they deserve when it comes to inventions, discoveries and research. To spread the news about women who spend their days looking through body tubes and using micropipettes, we’re going to feature a woman each month who proves that science isn’t just for the opposite sex.

Courtesy: painting by B.J. Donne (1847)

Mary Anning was a famous British fossil hunter, dealer and self-taught paleontologist who spent her entire life in the coastal town of Lyme Regis in Dorset, England. Growing up poor and without schooling, few could have foreseen that young Mary would someday make such significant contributions to the fields of geology, biology and paleontology and advance understanding of the evolutionary process.

Mary Anning was born in 1799 to Richard and Mary “Molly” Anning. Her father was a cabinetmaker who occasionally hunted for fossils and sold them to tourists to help make ends meet. The Anning family faced more than their share of hardship. Richard and Molly had ten children, but only Mary and her brother Joseph lived to adulthood. The two would occasionally join their father to search for fossils dating back to the Jurassic period in the rich marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel. Richard died in 1810 after a fall from one of Lyme Regis’s famed cliffs. After Richard’s death, the family was destitute, so Mary and her brother took up their father’s dangerous work searching for and selling fossils.

Stories from Mary Anning’s young life read almost as mythology. When she was just over one year old, Mary was being held in a neighbor’s arms when the woman was struck by lightning and killed. Miraculously, Mary survived and, according to family lore, the lightning strike transformed her from a sickly baby to a bright and curious child. From birth, Mary had two things working against her; she was from a poor family, and she was a girl. She had almost no access to formal education because she had to work, even as a young child, to help support her family. In fact, in Mary’s day, women were not allowed to attend a university. She didn’t let that stop her, though; instead she taught herself to read and write.

Mary is credited with having discovered the first complete Ichthyosaur fossil when she was only about eleven years old, though many sources say that her brother Joseph was actually the first to discover the creature’s huge skull. Mary, however, discovered the rest of the Ichthyosaur and did the painstaking work of chipping the fossil from the seaside cliff wall. Mary also determined that, what was assumed to be a fossil of an alligator, was actually a Jurassic dinosaur never before seen in its entirety.

How did an impoverished girl with little schooling know so much about dinosaur fossils? She worked her butt off, of course! Mary not only found and sold fossils, she studied and learned from them. She compared the specimens and noted their similarities and differences, read as much as she could about geology, biology and paleontology, and consulted with other, formally trained, scientists. A handful of noted scientists even took trips to Lyme Regis to meet Mary, study her fossil specimens, and compare findings with her.

*Hugh Torrens, Department of Geology, Keele University, Staffordshire, England, 1995.

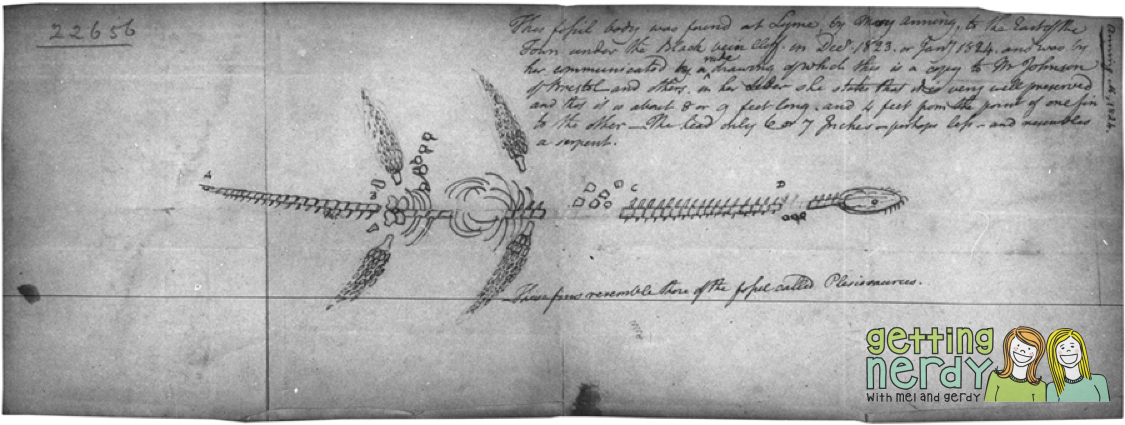

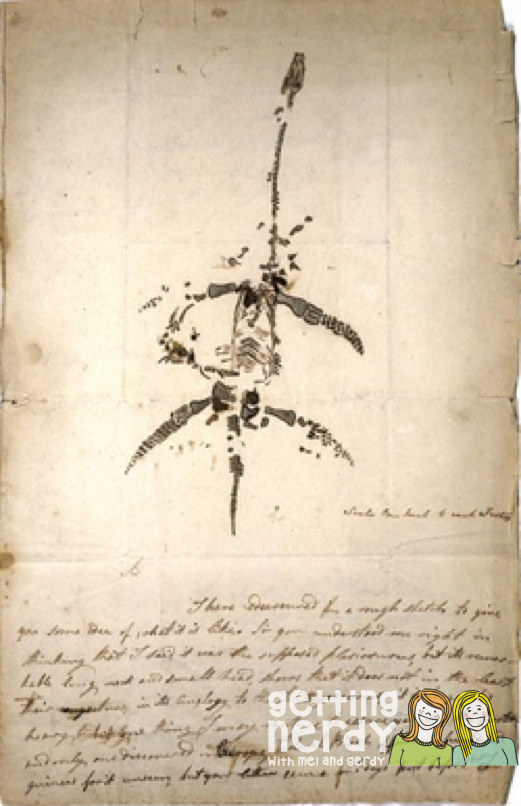

Mary Anning went on to make more amazing discoveries, including several other well-preserved Ichthyosaur skeletons. She was known throughout England as, quite possibly, the best fossil hunter and dealer alive. Still, many scientists of the day continued to attribute her success to luck or even divine providence. However, it was Mary’s discovery of the first Plesiosaur fossil that finally earned her respect from the scientific community.

Sadly, Mary Anning died at only 47 years old from breast cancer. Her obituary appeared in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society in 1847, despite the fact that the organization did not begin to admit women until 1904.

After her death, Mary was all but forgotten by scientists and historians and the great majority of her discoveries ended up in museums and private collections with no attribution to her. It is only in the last few decades that Mary Anning’s vast contributions to science have been acknowledged and fully appreciated.

Want more? Check out this Youtube video all about Mary!

Inspire Students. Love Teaching.

We have everything you need to successfully teach life science and biology. Join over 85,000 teachers that are seeing results with our lessons. Subscribe to our newsletter to get a coupon for $5 off your first order!