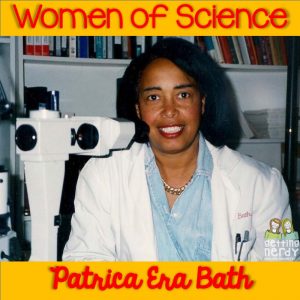

Patricia Era Bath was born in 1942 in New York City to Rupert and Gladys Bath. Her father was an educated man with wide-ranging work experiences. He was the first African-American motorman on the New York City subway system, a newspaper writer, and a merchant seaman who traveled the world, fascinating Patricia with stories of his travels. Her mother Gladys, a descendant of African slaves and Cherokee Native Americans was a stay-at-home mom who went to work as a housekeeper to help pay for Patricia’s education. She was a passionate reader who nurtured her daughter’s love for books and encouraged her interest in science by buying her science books and a chemistry set.

Patricia Era Bath was born in 1942 in New York City to Rupert and Gladys Bath. Her father was an educated man with wide-ranging work experiences. He was the first African-American motorman on the New York City subway system, a newspaper writer, and a merchant seaman who traveled the world, fascinating Patricia with stories of his travels. Her mother Gladys, a descendant of African slaves and Cherokee Native Americans was a stay-at-home mom who went to work as a housekeeper to help pay for Patricia’s education. She was a passionate reader who nurtured her daughter’s love for books and encouraged her interest in science by buying her science books and a chemistry set.

When Patricia was growing up, there were no high schools in her predominantly black neighborhood of Harlem. Patricia knew of no female doctors and surgery was an almost completely male-dominated field. Additionally, African-Americans were excluded from many medical schools and medical societies. Despite this lack of role models who looked like her, she was determined to become a physician after reading newspaper stories about Dr. Albert Schweitzer famous for treating people with leprosy in Africa.

Patricia was both a gifted student and a hard worker determined to reach her goals. She excelled in high school, completing her studies in 2 ½ years, before moving on to college at Howard University in Washington, DC. At just 16 years old, she was already working in the field of cancer research and receiving science awards for her work.

Patricia returned to New York City in 1968 where, as a young intern, she shuttled between Harlem Hospital and Columbia University where she’d been awarded a fellowship. Working in these disparate neighborhoods, she noticed her African-American patients were far more likely to suffer from visual impairment or blindness than white patients. She conducted a study that documented cases of blindness among blacks were double that of whites. She reached the conclusion that this disparity was due to a lack of access to ophthalmic care in poorer neighborhoods. As a result, Patricia championed the concept of community ophthalmology, a volunteer-based outreach that continues today providing low or no cost ophthalmic care to underserved communities. This outreach has saved and even restored the sight of thousands of people who would have otherwise gone undiagnosed and untreated.

Patricia served her residency in ophthalmology at New York University, the first African American to do so in her field. Patricia went on to become the first woman faculty member at the Jules Stein Eye Institute at UCLA. Even in her success, she faced racial and gender discrimination. When she first joined the faculty at UCLA in 1975, she was initially offered an office that was, she said, “in the basement, next to the lab animals.”

Patricia served her residency in ophthalmology at New York University, the first African American to do so in her field. Patricia went on to become the first woman faculty member at the Jules Stein Eye Institute at UCLA. Even in her success, she faced racial and gender discrimination. When she first joined the faculty at UCLA in 1975, she was initially offered an office that was, she said, “in the basement, next to the lab animals.”

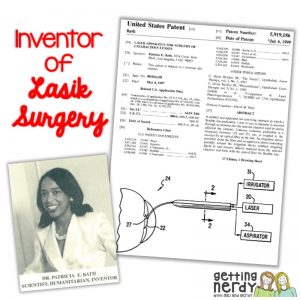

Patricia spent years traveling the world, offering her services and bringing awareness to vision issues before returning to UCLA to focus her research on treating cataracts disease in the United States. Cataracts causes cloudiness in the lens of the eye resulting in blurred vision and often leading to blindness. In addition to being a pioneering physician and researcher, Patricia became an inventor, devising a safer, faster and more successful approach to cataracts surgery using what she called a “Laserphaco Probe.” Patricia holds patents in the United States and around the world for her invention. While Patricia is now retired from UCLA, she continues to advocate for vision issues and vision care outreach.

Though Patricia faced gender and racial-based obstacles in her career, she’s always prefered to focus on the work, saying, “Yes, I’m interested in equal opportunities, but my battles are in science.”

Inspire Students. Love Teaching.

We have everything you need to successfully teach life science and biology. Join over 85,000 teachers that are seeing results with our lessons. Subscribe to our newsletter to get a coupon for $5 off your first order!